This is a repost of something I wrote on my Facebook wall in February, but I’ve put it here for better visibility and sharing.

When a meme page exists that mainly spends its time savaging the membership and leadership of multiple LARPs in our community, and if you look at its metrics, this is what you see:

Amtgard is the largest LARP org page on Facebook. It has 8.2k followers. The MES’ page is 3.4k, one of the smallest national LARP org pages, while Dystopia Rising sits at 6.2k and NERO at 6.8k The biggest larp-related page period is Larping.org, at 12k. The largest LARP related group at all is the LARP Haven group at 13.8k.

By comparison, the page in question has gathered 1.4k 2.6k followers in what looks like 2 years – and it’s only really been active for the last year. Most of those pages above have been around over 7 years. At this rate of growth, the page is looking to eclipse all national campaign-style organizations within the year. It might have wider reach than pretty much any LARP org quicker than we think.

So, what does that tell us? That attacking our hobby is more popular than the hobby itself right now. People are gleefully treating attacks on the members and leadership of this hobby as a bloodsport, and like to watch it happen. The best way to get in good with the most LARPers the quickest is drag whoever they can onto the bloody sand and gut them in front of the crowd. And that crowd will laugh while you are doing it.

It’s impossible for them to be responsible for this. They couldn’t have created this situation. They are exploiting it, and will likely continue to exploit it so long as it feeds the dopamine kick of getting a reaction and watching their numbers climb. The crowd packs itself in to watch the show, gleefully mashing that Like and Share button like the plebian crowds in the Colosseum calling for the death of the loser in the arena.

They just happen to be good at it and know how to provoke a reaction. They know how to get their name said, and that’s by going after people’s egos and self-worth. They’ve read social media theory and guerilla marketing; and they’ve figured out how to slice right into the market they are targeting. It shows in how they modulate between light humor, self-effacing ‘that’s me’ posts and brutal savagery that provokes a reaction and throw red meat to the angry. And how they choose or create memes that are inkblot tests that anyone can project either themselves or their frustrations on. I’m even flattered they’ve flat out stolen a couple of my own creations. They are good. I’m impressed, but I know what they are doing for what it is, and I don’t like being manipulated.

But damn if they aren’t piercingly utterly tapping into the zeitgeist and saying the unsayable at times, and getting more of a reaction than ten years of LARP theory, scholarship and accusations with a name on them. But it is a bloodsport, and sometimes, it’s just butchery. And the crowd cheers. Oh, how it cheers, all the same.

The Colosseum and the crowds that packed it were not the fault of the gladiators or their organizers. The crowds in the arena were seeking succor from a decaying empire, rampant corruption, the cruelty of daily life. They accepted what was being done because they were ready to hate and dehumanize another person. The bloody games were a symptom, not a cause.

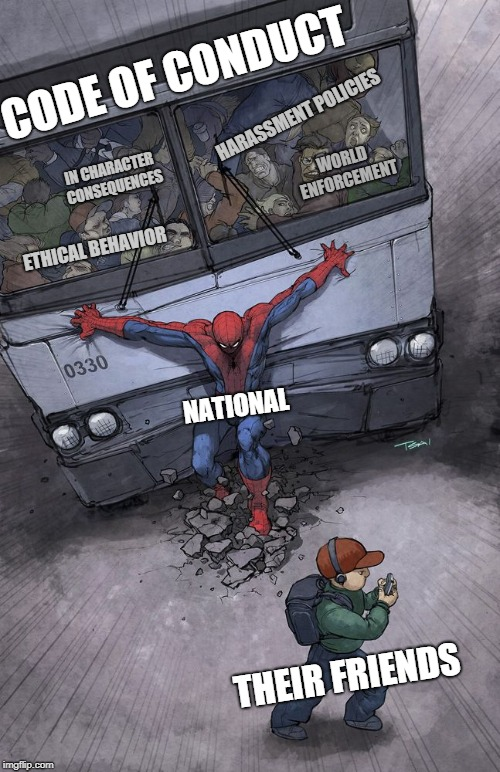

The solutions, those ‘constructive’ comments being demanded, are out there, gathering dust as they have for years. Articles, research, surveys They are literally everywhere. Even the ‘non-constructive’ comments show what the problems are, even though their solutions are often nasty and born of the very pain that fuels that arena. LARP organizations in the United States are remarkably resistant to change and defiant of critics.

Me, I’m tired of it. I don’t like or follow that page for a reason, and I’m not contributing to it. I’ll be running Cyberpunk in May, The Night in Question in November, and got other news on the way. And my players aren’t going to be as interested in seeing me laid out on the arena floor after playing in my games for a year or two. Or at least, I hope they aren’t.

I don’t fault anyone for following the page. They are funny, incisive and it’s a thrill to watch someone who deserves it get kicked up the backside. That’s been the foundation of comedy for years. But the solution is to address the problems, not put on blinders or ignore them; and maybe the dopamine kick we get from the viciousness isn’t worth it?

But in the end – are you not entertained?