Featuring a completely contrived but interesting Four Layer Model for Gameplay

So, I create LARP experiences, design games and the like. That means I think a lot about what makes something a game, and I like teasing out how systems work. Sometimes I do this just for fun, and sometimes it reveals some important things we should keep in mind when we are designing, running and playing games with each other.

A few years ago, I started unpacking the difference between a system and a game after reading the seminal and amazing book Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, a weighty 777 page tome about mathematics, rules and the nature of systems. And in spinning out these ideas, I came up with some categories of what goes into designing and playing a game. And I came to a beautifully weird conclusion –

I don’t design games. No one designs games.

We design systems – and we might suggest, cajole, pressure and clear our throats while nudging our head in the direction of how they might be turned into a game. But only a player can choose which game they play.

Beyond that, as a designer, I’m powerless. And that’s wonderfully humbling and utterly frightening.

Unpacking the Game Box

Now, going up to a game designer and telling them they don’t design games is a pretty bold move. It depends on a lot of definitions of what a game means, what rules mean, what a system means; and my choices of definitions here are just one option among many. But I think they tell us something useful about how playing games really works.

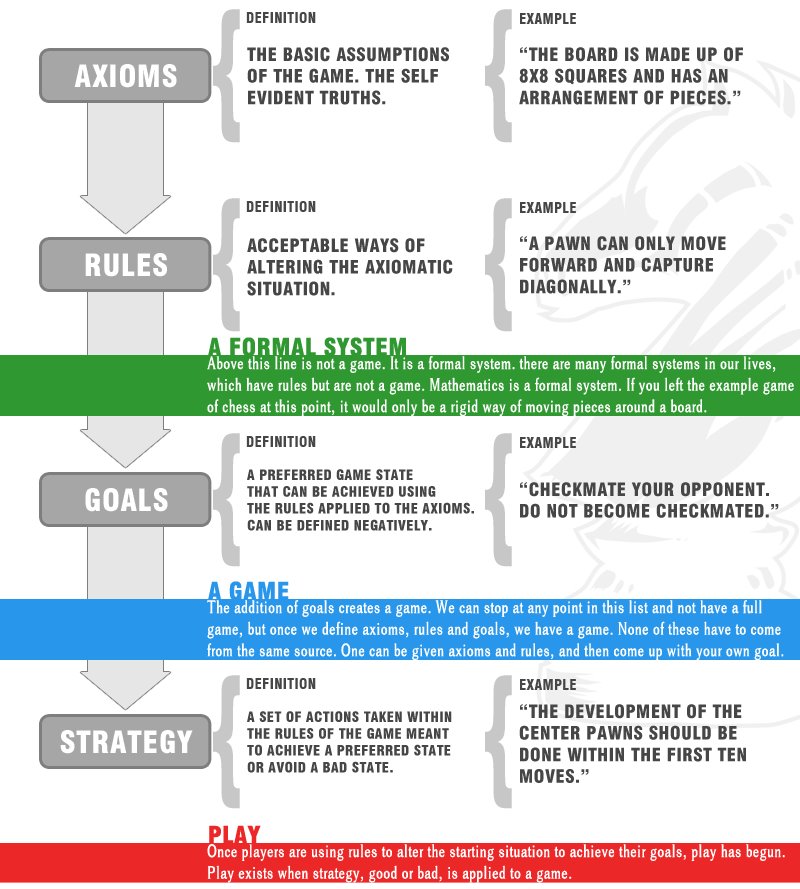

I made a chart. Charts help, right?

Okay, this one might create more questions than it answers. Let’s break it down. When you are watching a game being played, what you are seeing is players applying strategy to achieve goals using rules to change the state of the situation.

Imagine you are opening up a new board game. You unwrap the plastic wrap, enjoy that strange smell of Kickstarter-funded Chinese printing for a moment then proceed with the Herculean task of removing the top without tearing the cardboard due to the strange physics of air pressure.

You are confronted with a board covered with provocative artwork; plastic miniatures of fantasy creatures that most likely got you to throw down the $80 pledge and accept this experiment in risk and deferred gratification that is Kickstarter; a myriad of cardboard chits; usually some dice or cards; and a rulebook.

Set the rulebook aside. Let’s take a look at the rest. These are your axioms.

The Axioms

Every system starts with axioms. That board, those dice, those beautiful rendered molded plastic minions possibly doomed to be ruined on your painting table – those are all the axioms of the game.

An axiom is the base assumptions upon which any system is based. In mathematics, axioms are things like “x = x”, the baseline immovable concepts that are not challenged. Axioms in a game are the initial assumptions that are required for the game to move forward. Here are some games and their axioms –

- Chess: The board consists of 8×8 squares with a starting arrangement of 32 pieces, 16 black and 16 white. There are two players.

- Basketball: The game area consists of a standard-sized basketball court with two standard baskets. There is one basketball and two teams consisting of 5 players.

- Axis and Allies: There is a world map abstractly representing the years 1938-1945, and pieces for the armies, navies and air forces of the various Allied and Axis powers. There are two or more players, each controlling a single power. The German player is either slightly awkward or way too into it.

- Vampire the Masquerade: There are one or more characters represented abstractly by character sheets made using the Storyteller system, each under the control of a player. There is a Storyteller. There are a variety of 10-sided dice – not required to be black or marbled but that’s usually how it works out. I don’t know if painfully fake accents are axiomatic, but they might as well be.

- Cards Against Humanity: There are two decks of question and answer cards and at least two players. This game will get boring after 30 minutes and is not as funny in retrospect. (Okay, that’s not an axiom, but damn if it isn’t true.)

Some of what we call rules are actually axioms if we use the precise language for such things presented in Godel, Escher, Bach. They usually are under the setup part of the rulebook, or are signified by what we get in the game box itself. All the axioms put together are the axiomatic situation, the state every game begins in. If you start mucking around with the axioms, you’ve fundamentally changed the game. It would be like adding a third player to chess or injecting actual humorous content into Cards Against Humanity.

But we don’t have a game yet. We just have the starting state. Grab that rulebook now and flip open that glossy full color goodness printed in the fair People’s Republic that you waited a year longer than you expected for…

Rules, but still not a game

Any rule can be defined as an acceptable way of altering the game’s state. Whether it is passing your turn, rolling the dice to hit or moving the king one space per turn, a rule tells you what you are allowed to do within the system to change it.

So, you’ve set up your board game, figured out who goes first and put the pieces in their starting position. You’ve managed to read the setup rules despite the second cousin the game’s indie publishers employed not appreciating how poorly white text goes on colored backgrounds. You’ve done all the things you need to setup the axiomatic situation.

Now, what do you do? You start changing the situation. You roll dice and then move according to those dice. You build sheep, breed wheat and harvest roads. Whatever the rules allow you to do.

Cool. Now, here’s the crazy part…

You still aren’t playing a game yet.

Axioms define a starting state, then you use a set of rules to start altering it – but it’s not a game. It’s just a system. In mathematics, this is called a formal system. What we call rules is more formally called a grammar, a way of producing new situations from axioms or situations produced from those axioms. But grammar and formal system are kind of weird even for this level of theory, so system and rules is fine for us non-mathematicians out there.

But short version is – a system is a rigid way of altering the state. How and when you change what things is defined by that system. You can only move chess pieces a certain way on your turn, for instance. But you are missing an important thing: what state am I trying to achieve using the system?

In other words, what is the goal when using this rules? A game begins to exist within a system only when a goal is chosen or accepted by the player. And here’s where it gets weirder – each player can literally be playing a different game by choosing different goals, while inhabiting the same system and situation.

Goals and Weird Things To Do To Mario

“Hey, wait a second! The goal is just another part of the rules!” you say, being the hypothetical reader in my head whose voice is surely a sign of my empathy for my audience and not a symptom of early onset dementia.

Sure, the rules can attempt to tell you what the goals are, and can certainly tell you when a game ends. But there are games where the game ending is not the traditional goal, such as pinball, where the challenge is to keep playing as long as possible. A designer might frame their anticipatedgoals as rules but in the end, the players can still play a game within the formal system the designers have painstakingly crafted with completely different goals. This is an amazing and beautiful reality of game design – that we are only suggesting goals as designers, not dictating them. And it is a cool idea revealed by this model.

Let me take a brief segue into video games and talk about one of the odd ways our favorite plumber Mario has been used and abused over the years. This is just a case study in how weird it gets when the players get ahold of your system and decide to discard your meek and humble suggestions for goals in favor of going down their own bizarre rabbit hole.

Mario’s Race to the Bottom

The weird world of speedrunners, streamers and next level video game enthusiasts provide plenty of examples of gamers using a system to play very different games. You find challenges to create weird glitches; attempts to unlock strange ‘losing’ endings; or just to pervert the game to its extremes. Sometimes, altering the goal just means adding extra challenges – such as attempting to play Punchout blindfolded – but the most interesting one to me is the Low Score challenge around the Super Mario Brothers franchise.

Several years ago, gamers hit upon a goal that profoundly altered the gameplay and strategy of Super Mario Bros. The goal was to complete the game and get to the Princess with the lowest possible score. The current record is 700 points, and that is after years of challenges, attempts and strategies developed by numerous players in a rather heated and intense competition.

No one on the game design staff could have predicted this bizarre goal yet nothing in the game’s system prevented it from becoming one. This was a perfectly valid goal, and the game designers had no say in it.

Why is this important?

“Okay, so, video game geeks are weird, what does this have to do with me as a designer or player in board games, RPGS or LARPs?” you reply. I’m glad you asked, magic voice.

This is a deceptively important point to make about goals in games. If players are not convinced to pursue your stated goal, it doesn’t stop them from playing inside your system. They just aren’t going to make the choices or enact the strategy you anticipated them using. This can create weird and possibly damaging consequences, especially if your games involved large numbers of players.

Alternative goals that show up in games include griefing (trying to frustrate other players as much as possible); aesthetics (building your city or designing your deck to look pleasing to the eye or incorporate some sort of aesthetic theme); perverseness (I wonder what would happen if I try to win with just peasant units) or just arbitrariness (I like red things so I’m going to collect all the red markers).

What this really emphasizes is that player buy-in is extremely important if a common goal is necessary for your LARP event, RPG, megagame, etc. to really work. You can never force a player to accept a goal just through the system. You can make certain goals harder or impossible, but you can never make them accept your goal. And you can’t limit everything to just one goal, really. The above Mario challenge proves that even if you put up a scoreboard, the goal to get the lowest score is just as valid as striving for the highest one.

What you can do as a designer is offer multiple goals and incentivize them. Even then, you reach your limits very quickly. It’s a good idea to support multiple kinds of goals and ends within more abstract social games such as tabletop RPGs or LARPs, specifically because these are open-ended games that attract multiple types of players. This still won’t solve your problem, but it will give people more options of anticipated goals to pursue and make it more enjoyable.

Game organizers and community managers are the ones in a position to actually ensure player buy-in, either by removing players who don’t pursue the same goals, or even better, convincing players about the correct goals to pursue through education.

Strategy and Alternative Goals

When you play a game, it means you are applying a strategy in how to use the rules to move the situation into a preferred state or avoid a bad state. Those states are determined by your goals.

Usually, alternative goals are fairly harmless. But the more players and more moving parts exist in a design – especially in LARPs or multiplayer competitive video games – the more pursuing malignant alternative goals can be disastrous for a gaming community. Because when people are literally not playing the same game, that may mean they aren’t compatible.

Let’s imagine a multiplayer base-building team game. A typical player who accepts the game’s basic goals of “join teams and help your team win” will want to join a team and build a strong effective base in an attempt to win the match. A griefer has an alternative goal – “frustrate other players and sabotage them for your own enjoyment” – so they will want to join a team in order to gain their trust then cause maximum damage and render the team’s efforts pointless as an opportune time. A single griefer pursuing these goals can ruin everyone else’s time, so goal buy-in is important.

The big take-away of the impotence of rules to govern the goals is that handling players who are pursuing malignant goals that are destructive the experience of other players is primarily a community management problem, not a game design problem. Game design can help, especially by avoiding setting up stated or implied goals which cannot coexist peacefully. But the bulk of the work is in ensuring players are not pursuing maladaptive alternative goals through oversight. That oversight can be as simple as coaching a new player at your table on good behavior; or as complicated as managing a international MMO community.

It’s not necessary to punish any alternative goal, but you have to manage your community in such a way that punishes goals that produce strategies that have a direct negative impact on players pursuing your preferred goals. But be too strict or allow your own players to police for the proper goals too much, and you aren’t allowing your system or world to be truly explored.

Alternative goals can produce beautiful and interesting variations in strategy and thus play. Tabletop roleplaying itself arose from players pursuing the alternative goal of telling a hero’s story using wargaming rules. So, don’t be afraid to embrace and explore alternative goals and the alternative strategies they produce.

Matthew Webb organizes live action roleplaying (LARP) events with his team at Jackalope Live Action Studios in Austin, TX; and creates augmented reality software at Incognita Limited. He can be found on Facebook and Twitter. Learn about their upcoming events by following Jackalope Live Action Studios on Twitter (@JackalopeLARP) and Facebook. All opinions here are his and his alone.